It's Thanksgiving morning and I drive the sixty miles to the retirement

home where my eighty-four-year-old mother lives. We, together, then travel another one hundred

forty miles to the town where she gave birth to my brother and me. We go there to share the holiday with my

father's sisters and their husbands. We

will retrace our steps this afternoon so that we can sleep in our own beds

tonight.

This assemblage is all that is left of my parents' generation in my

small family, and the planning has been fraught with angst and last minute

changes of heart. My mother has been

sick and has recently fallen. She

commits, is then ambivalent, finally deciding to attend at the last minute,

afraid that she will miss what may be her last visit with the group

intact. My father had three sisters, all

still going strong, the baby being a mere eighty-three. The two who married have husbands who, God

willing, will soon attain the age of ninety.

Although small in number and now in stature, they are intrepid souls,

each placing one resolute foot before the other as another holiday season rolls

around at breakneck speed. At my callow

age, I am the only one who drives with any impunity so it makes sense for me to

deliver my mother.

I have a hidden agenda. Although

I am happy (and sad) to see my aging relatives, aware that these gatherings

have a limited future, I am here for information. I want the scoop and time is of the essence.

I have only recently become interested in oral history, in family lore,

too late to ask my father. Having talked

my poor mother mute with requests for stories of her childhood, I am moving in

for the kill on my only link to my patriarchal side. My quarry are unsuspecting as they masticate

their Chex Mix and drink their Bloody Mary's, their thoughts centered on

survival issues like social security, high prices and poor service.

I point to an old family portrait, hoping to spark a natural segue. As we all gather in a corner trying to look,

I become confused and a bit claustrophobic.

"Who is that?" "I

don't know." "That's

Granddaddy." "Which

Granddaddy?" Adding to the

befuddlement is the family penchant for reusing names. "That's Susie." "Which Susie?" "Is that me?" "No, you weren't even born

yet." The people in the portrait gaze stolidly back at me, unmoved by my

distress, people who, although still unnamed, look disconcertingly very much

like us.

I haven't yet mentioned my objective for the day, nor have I produced

the tape recorder. We have had some

discussion about my digital camera, the consensus being that, with its preview

and deletion capabilities, it is a good thing.

That is until I mention that it works best when affiliated with a

computer.

As we gather at the table, I get up the nerve to mention that I am

interested in hearing the stories of my aunts' childhoods. My middle aunt, the one hosting our feast,

says, with some vigor, "I have

always said that, if someone wanted to write stories, we have

stories!" But before I can get my

tape recorder out from under my chair, the talk turns to which aunt made the

salad and is the meat cooked to everyone's taste. The uncles are contentedly eating, dabbing

their mouths, passing the bread. Thinking that it might not be nice or smart to

try to control the dinner conversation, I decide to hold off until dessert.

As we choose between rum cake and pecan pie, I lay the tape recorder on

the table. It looks out of place on the

snowy cloth, the black plastic defiling the aura of the autumnal

centerpiece. My mother smiles

encouragingly at my aunts, glad that it is they for whom the recorder records

and not she. They utter a collective

sigh, as if steeling themselves for something that they just can't seem to

escape. Resorting to form, my middle

aunt attempts to get things started, asserting, a bit protectively, that they

had a wonderful father and a great childhood even though they were motherless

and poor. My oldest aunt, the one who

never married, looks vague and says that she can't remember much. The baby says that she just isn't good at

telling stories. I ask specific

questions, just trying to get the players straight. I learn that, after the death of their

mother, an aunt and her son came to live with them. The son, their cousin, was like another brother

to them and my daddy was very glad to have an additional boy, a compatriot, in

the house. After a few more helpful

facts but no real stories, the talk turns to contemporary matters and we finish

our meal by lining up to talk on the phone to my brother who is eight hundred

miles away. I put away the tape

recorder, pondering when I can schedule a return trip to talk to my father's

sisters individually.

Making our way back to the den for coffee, I can tell that my mother is

tired and I think of the long drive ahead.

It's time to take our leave. In

gathering up my paraphernalia, I deposit the scorned tape recorder in the

bottom of my bag. Before adding the

digital camera, I show my youngest aunt the picture of my Labrador Retriever

that I had taken just before leaving home, a practice shot to make sure the

battery was charged and the disk had space for the family pictures that I would

take. As we begin heading toward the

door in a sluggish throng, my aunt says,

"I remember that we had animals.

I had a dog named Diddiebycha (as

in Did he bite ya?) and George" (her brother and my father) "had a

cat named Black Cat Kitty." My

middle aunt says, "I remember that too.

George also had a big dog named Fritz.

And Earle" (the cousin) "had a bulldog named Pat." A look of amusement settling around her eyes,

she asks my other two aunts, "Do

you remember the time George came home and found Pat in his bed with a note from

Earl that said, 'Don't move Pat. He got

run over by a fire truck.'" They

nod, smiling, their faces rapt.

I perk up at the splendid story, wishing that I could dislodge the

recorder from the bottom of my bag, but I'm afraid of breaking the spell. As they continue, I find that Pat survived

being run over by the fire truck and that my daddy endured the indignity of

having a dog appropriate his bed. As if this were not enough, as if this story

wasn't worth the trip and putting my poor relatives through a stressful and

strange holiday get-together, my oldest aunt, the one who earlier couldn't

remember, the one who never married, stands up, grasps a chair arm to gain her

balance and announces with some surprise and a great deal of enthusiasm,

"I had a goat!"

As we pass through the back door, sharing hugs and promises of future

occasions, I am reminded why family is so important and why it is worth the

time and energy to make these trips. I

am also reinforced in my, sometimes, misguided attempts to hear the stories of

my antecedents and to share those stories with my own children. Although we have learned about the era of my

father's youth in our history books, we know little about what it was like to

live in that time in a family torn apart by illness and economic decline in a

small town in South Georgia. We need to

learn all that we can about a certain motherless family, which happens to be

our family, that was presided over by an overwhelmed father who loved his

children and allowed them pets, including an injured bulldog in a boy's bed and

a goat for a little girl who would never marry.

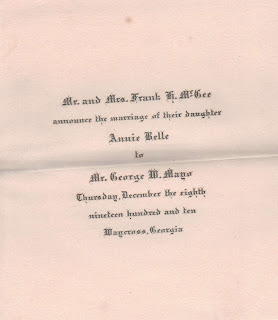

My grandparents' wedding announcement

My grandmother, Annie Belle McGee Mayo

My grandmother's death announcement

Susie, Daddy, Aunt Annabelle, and Uncle Bill