In honor of the trip Joe and I are getting ready to embark upon, I decided to re-visit the story I wrote about going to Oak Creek with mama - the only time I went there with her other than when we all went for her funeral. I think I had to do some editing for publication in Arizona Highways but this is the original version. Oak Creek will always be a sacred place for me.

I always knew about Oak Creek, where my mother spent her

summers as a child and where she took my daddy just after she married him,

before he, in turn took her east to start their life in Georgia. For me, it has a mysterious, almost mythical

allure. Of course, I knew only what I

had heard from Mama and what I had seen in the sepia-tones photos stored in our

attic.

In my mind, I saw Oak

Creek as being from another time, a time when the west

was still wild, a time when a little girl could grow up hunting, fishing and

camping – real camping, not Winnebago camping.

For me, a product of the 1950s, a child of the South, Mama’s stories of

staying at Oak Creek

in the 1930s and ‘40s were as foreign as if she had been raised by wolves. Perhaps

she was. It could happen at Oak Creek.

It wan not until years later that I, as the mother of a

daughter myself, yet still a daughter to my own mother, made the trip to the

place that was so much a part of me, even though I had never been there. Three generations of females flew west from Atlanta in the spring of

1998. Mama, my 13-year-old daughter,

Molly, and I all had different agendas.

My mother wanted what might very well be her last visit to her home

state, and I longed to know more about her early life. I wanted to find myself somewhere in her

beginnings, to know the “Arizona

part” of me. Molly came only because I

wouldn’t let her stay home with her friends, even though she thought she was

old enough.

The three of us traversed the circuit of my mother’s

childhood, starting with Prescott,

where she was born. Her family’s

Victorian house still stands, now listed on the historic register, but in

tawdry disrepair.

Next we went to Flagstaff and

visited the University

of Northern Arizona,

where Mama earned her teaching degree.

As we neared Oak Creek,

our anticipation became palpable, at least for my mother and me. Molly was busy experimenting with different

makeup looks in the back seat of the rental car, a Walkman firmly affixed to

her ears.

Mama had saved the best for last. We were to stay in a motel on the edge of the

enigmatic Oak Creek

and would visit Sedona and take a day trip to Jerome, the played-out mining

town where she had grown up, living on that portion of the mountain known as Cleopatra

Hill. Throughout the week, as we took in

the sights and mused over almost forgotten memories, Mama kept saying, “I just

hope we can find where the Oak Creek

cabin used to be. That’s what I want to

see most.” I hoped so, too, mostly for

her, but also for me.

The Oak Creek of Mama’s childhood was very different from

today’s vacation and retirement mecca of Sedona. In the old days, it was a place of hardy

locals mixed with folks, like my grandparents, who camped and built summer

cabins on the edge of the creek, within view of the majestic red rocks. It seemed the place that defined her

most. She and her daddy had helped to

build their cabin on a site so pristine and beautiful, so geographically and

aesthetically desirable that few could afford it today.

Mama knew the cabin had been torn down and the land returned

to the state at the end of a 99-year lease, but she hoped for some sign that

her life there had really happened, perhaps some proof for me.

Descending the winding road from Flagstaff,

I thought this had to be the most beautiful place in the world, this land of Oak Creek. Mama couldn’t seem to take it all in. She kept craning her neck, looking for the

place where the cabin had stood. “Maybe this is it. No, it doesn’t look right.” Small access roads, leading toward the creek,

all looked the same to me. For her, it

had just been too long and things had changed so much. No doubt some of Mama’s memories had been

distorted by time. We stopped and asked,

but no one could help us. The old-timers

were gone.

The next day we stopped in Clarkdale for lunch and then

headed up the mountain that was, and still is, Jerome. I saw the “J” at the top. Mama had told me how painting the inscription

had been a high-school freshman class rite of passage. As I peered over the dash at the steep climb

up to town, I remembered why Mama never learned to ride a bike as a child,

finally mastering it as an adult in the flat marshlands of South

Georgia. Bike-riding in

Jerome was dangerous, if not impossible.

After attempting to park the rental car on a downhill slant and close

its door without losing my footing, I understood.

Mama’s daddy had been the city attorney in Jerome before

moving to Phoenix

to become an assistant state attorney general.

I recalled the story of the jailhouse sliding down the mountain and

remembered how I had surmised in my egocentric child-mind that my granddaddy

probably had some “worthless varmints” incarcerated in the jail as it made its

way to its new address. Learning in

later life that my grandparents had already moved when the jailhouse made its

way down Cleopatra Hill was a little disappointing, so I chose to remember it

the other way. I also, as a little girl,

possessed some primal narcissistic sense that Jerome’s slow descent down the

mountain and its ultimate decline in population had to be connected in some way

to my grandfather’s ascent up the ladder of success elsewhere. My family’s moving on had to have been the

last straw, an abandonment with which the town just couldn’t cope.

I found Jerome to be interesting, yet felt sad that it had

changed so much since my mother’s day. I

was glad that the artists had utilized its charm, but couldn’t get past how

difficult it would be to live in Jerome, forever canting one way or another,

afraid of losing one’s grip, not only on reality but also on the Earth

itself. I can see why Mama holds on so

tightly to life and why Oak Creek

became such a compelling resting place for her.

On our last morning, we awoke to a light snowfall. Although it was pretty and its arrival in

mid-April a novelty to us Southern marsh hens, it also hinted at a

disappointing final search for the bygone cabin at Oak Creek.

I worried that the drive back to Phoenix

would be difficult in the snow. Molly

was having trouble with her lip liner.

Mama asked that we look one last time.

Turning back toward Flagstaff,

I feared that Mama would be terribly disappointed if we couldn’t locate the

site. All I could see was snow, and

driving in this kind of weather makes me tense.

About a mile up from the motel, Mama pointed to a side road, more like a

driveway. This was one of the places we

looked earlier, one of the many that seemed almost right, but not quite.

We pulled over and got out of the car. I envisioned broken hips from falling in the

snow and wondered how difficult it would be to get an ambulance up this

slippery road. My mother carefully made

her way over to a fence. “This has to be

it. I just wish I could get closer.”

As she and I gazed forlornly over the frustrating barrier,

trying to see what might have been vestiges of the cabin, Molly unfolded from

the back seat and out of her adolescent self long enough to check a spot where

the fence had collapsed. “Why don’t we

just try that hole in the fence over there?”

It took just seconds to mull the repercussions of

trespassing on state land and then for all of us to transcend the broken-down

fence to Mama’s childhood – and my Arizona

roots.

As soon as she reached the concrete slab just a few feet

from sparkling Oak Creek,

Mama knew she was home. Her faced

wreathed in smiles, she cried, “This was the cabin’s foundation! This was the terrace!” It even looked right to me. It looked like the photographs from the

attic. All the tableau needed was for my

grandmother and my grandfather and my honeymooning father to join my mother in

repose as they had in those pictures taken so long ago.

From there, we walked over to the waterwheel my mother and

grandfather had built to generate electricity for the cabin. That’s when I knew, for sure, we were in the

right place. I had heard about that waterwheel my entire life. It was surreal, actually being there, really

touching it. Mama was surprised it had

survived nearly 60 years, as the snow’s melting each spring had continually

kept if flooded and in disrepair. When I

saw it still standing, it seemed to me that its real purpose may not have been

so much pragmatic as commemorative. We

had found evidence that my mother’s Oak

Creek was more than just a place in time. Oak

Creek was basic to the woman she had become, the woman

who loved my daddy and who bore my brother and me in a very different place and

time.

Just before leaving, Mama pointed out the cliff cave on the

other side of the creek that she, at 13, used as a refuge from a mother and

father who simply didn’t understand, just as Molly’s parents currently

didn’t. With that comparison, it became

clear to me that the beat of my mother’s heart and the essence of what it takes

to be a woman reverberated from her, through me, to Molly, and would most

likely endure through other generations.

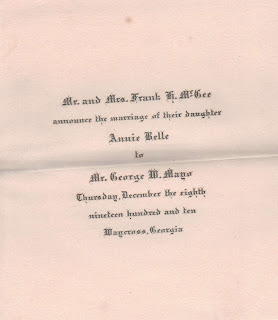

Mama fishing

Dadding and Daddy

Mama, Dadding, and Daddy

Going back to Oak

Creek that snowy spring was the right thing to do for

my mother. She needed to remember all

that endowed the girl she once was and the remarkable woman she grew into. The trip was, most definitely, the right

thing for me. I needed to see how the

creek water and the red rocks fed my Southern soul. It was also the right thing for Molly –

although she doesn’t know it yet.

Mama, Molly, and me at lunch in Sedona - Spring of 1998

I can't believe Melissa found the spot on her family trip East. Georgia and Miles on the cabin foundation at Oak Creek. January 2012